1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Semyon Bychkov

This time, chief conductor Semyon Bychkov has decided for an unsurprising but purely dramatic programming arch. We will hear concertos by Antonín Dvořák and Johannes Brahms, artistic colleagues and friends for many years. Czech Philharmonic concertmaster Jan Mráček will play Dvořák’s Violin Concerto, and at the piano in Brahms will be seven-time Grammy Award winner Emanuel Ax.

Programme

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53 (32')

— Intermission —

Johannes Brahms

Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 15 (44')

Performers

Jan Mráček violin

Emanuel Ax piano

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

In 1877, when Dvořák’s application for financial support and the score of his Moravian Duets were received by the committee in Vienna in charge of granting stipends, the jury member Johannes Brahms arrived at the opinion that Dvořák deserved more support. “He is definitely a very talented artist. And poor, incidentally. Please consider that!” Brahms wrote in a letter to his publisher Simrock. That was the beginning of Dvořák’s international success, and also of a 20-year friendship between the two composers.

It was also thanks to Brahms that Dvořák met the violinist and teacher Joseph Joachim. The first violinist of the Joachim Quartet, he premiered some of Dvořák’s chamber works, helping to spread awareness of his music. When Simrock commissioned a violin concerto from Dvořák in 1879, the composer reached an agreement with the famous virtuoso in Berlin that he would give the premiere.

Work on the composition proceeded slowly because Joachim returned the concerto to the composer several times with comments encouraging Dvořák to revise the work repeatedly. In the end, at the premiere in October 1883, instead of Joachim, the soloist was František Ondříček, to whom Brahms later also entrusted his Violin Concerto.

Joachim already had a major impact on the life of Johannes Brahms in his youth. He introduced the 20-year-old composer to Robert Schumann and his wife Clara, who later became one of the first interpreters of Brahm’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor.

The American pianist Emanuel Ax was already developing an intense relationship with Brahms at the conservatoire Brahms: “I already fell in love with his music as a teenager. From my parents, I had a recording of Rubinstein’s interpretation, and I wore out the grooves of two copies by playing them over and over.”

Besides having recorded both Brahms concertos, Ax has recordings of many of his chamber works to his credit. For recording the Brahms sonatas for cello and piano with the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, he received three of his seven Grammy Awards.

Performers

Jan Mráček violin

The Czech violinist Jan Mráček was born in 1991 in Pilsen and began studying violin at the age of five with Magdaléna Micková. From 2003 he studied with Jiří Fišer, graduating with honors from the Prague Conservatory in 2013, and until recently at the University of Music and the Performing Arts in Vienna under the guidance of the Vienna Symphony concertmaster Jan Pospíchal.

As a teenager he enjoyed his first major successes, winning numerous competitions, participating in the master classes of Maestro Václav Hudeček – the beginning of a long and fruitful association. He won the Czech National Conservatory Competition in 2008, the Hradec International Competition with the Dvořák concerto and the Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra in 2009, was the youngest Laureate of the Prague Spring International Festival competition in 2010, and in 2011 he became the youngest soloist in the history of the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra. In 2014 he was awarded first prize at Fritz Kreisler International Violin Competition at the Vienna Konzerthaus. When the victory of Jan Mráček was confirmed, there was thunderous applause from the audience and the jury. The jury president announced, “Jan is a worthy winner. He has fascinated us from the first round. Not only with his technical skills, but also with his charisma on stage.”

Jan Mráček has performed as a soloist with world’s orchestras, including the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony, Symphony of Florida, Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra, Kuopio Symphony Orchestra, Romanian Radio Symphony, Lappeenranta City Orchestra (Finland) as well as the Czech National Symphony Orchestra, Prague Symphony Orchestra (FOK), Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra and almost all Czech regional orchestras.

Jan Mráček had the honor of being invited by Maestro Jiří Bělohlávek to guest lead the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in their three concert residency at Vienna’s Musikverein, and the European Youth Orchestra under Gianandrea Noseda and Xian Zhang on their 2015 summer tour. He has been a concertmaster of the Czech Philharmonic since 2018.

In 2008 he joined the Lobkowicz Piano Trio, which was awarded first prize and the audience prize at the International Johannes Brahms Competition in Pörtschach, Austria in 2014.

His recording of the Dvořák violin concerto and other works by this Czech composer under James Judd with the Czech National Symphony Orchestra was recently released on the Onyx label and has received excellent reviews.

Jan Mráček plays on a Carlo Fernando Landolfi violin, Milan 1758, generously loaned to him by Mr Peter Biddulph.

Emanuel Ax piano

“Within minutes, we are totally captured by his intensity and pianistic achievement,” wrote the Los Angeles Times about the 74-year-old pianist Emanuel Ax. “Manny”, as he is sometimes called, is regarded as one of today’s most sincere and modest artists despite having been in the limelight of the worldwide music scene since 1974, when he won the inaugural Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Competition in Tel Aviv. He even has a fan club, “Manny Ax Maniacs”, the members of which wear t-shirts bearing the club’s name to his concerts.

Emanuel Ax was born in Poland, but as a young child he moved with his parents first to Canada, then to New York. There, he studied at the Juilliard School, where he now teaches, and he gave his concert debut as part of the Young Concert Artists Series. Victory at the Rubenstein Competition along with the Michaels Award of Young Concert Artists and the Avery Fischer Prize catapulted him onto the concert stage, where he achieved success of the highest order as a soloist and in chamber music.

Also of importance to his career was his partnership with the Sony Classical label, for which he has been recording exclusively since 1987. He even won a Grammy for his second and third albums in a series of Haydn piano sonatas. He also won this most prestigious of recording prizes for albums of the Beethoven and Brahms sonatas for cello and piano, which he recorded with Yo-Yo Ma, his long-time artistic partner. Ax, Yo-Yo Ma, and Leonidas Kavakos also recently launched an ambitious project to play all of Beethoven’s piano trios as well as his symphonies arranged for those forces. They are now promoting the project, known as “Beethoven for Three”, with live concert performances. So far, they have recorded symphonies nos. 2, 5, and 6 along with the Op. 1 piano trios.

Besides the traditional repertoire (or arrangements of it), he also devotes himself very intensively to premiering new works by contemporary composers. For example, he has been the first to play new works by such composers as Krzysztof Penderecki and John Adams; in October 2023 he gave the premiere of Anders Hillborg’s Piano Concerto No. 2, “The MAX Concerto”, written by that contemporary Swedish composer on commission for the San Francisco Symphony led by Esa-Pekka Salonen. In addition, this season has featured a European tour (mainly with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Bavarian State Orchestra) and a series of Beethoven-Schoenberg recitals around the USA, where Ax lives (in New York) with his wife, the pianist Yoko Nozaki.

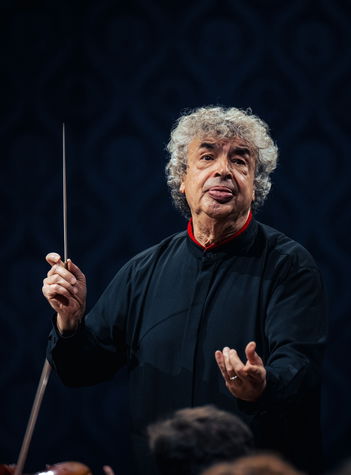

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53

Personal relationships, friendships, and mutual respect among individuals leave a more tangible imprint on history than one might expect. An illustrative chapter of music history involved Fritz Simrock, Antonín Dvořák, Johannes Brahms, Robert and Clara Schumann, and Joseph Joachim.

Among the compositions for solo instrument and orchestra by Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904), three concertos stand out: the Piano Concerto in G minor (Op. 33), the Violin Concerto in A minor (Op. 53), and the Cello Concerto in B minor (Op. 104). The first two date from almost the same period and were both actually published in 1883, but they underwent a different genesis. While Dvořák apparently came up with the idea of composing the early version of the piano concerto in 1876 on his own, perhaps fondly imagining Karel Slavkovský at the piano, the stimulus for writing the Violin Concerto in A minor was external. The publisher Simrock commissioned the increasingly popular Czech composer to write another composition of “Slavonic” character. The Czech Suite, Op. 39, the Slavonic Rhapsodies, Op. 45, the Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, and the String Quartet in E flat major, Op. 51 were all earlier works by Dvořák that were popular items on the sheet music market and were influenced by the melodic and rhythmic patterns of the folk music of the Czechs, Moravians, and other Slavic peoples. The violin virtuoso, conductor, and director of the Hochschule für ausübende Tonkunst Joseph Joachim, whom the composer had met in early April 1879 in Berlin, also supported the idea of a new concerto. The concerto’s dedication to Joachim shows Dvořák’s regard for the chance to collaborate with the legendary violinist and pedagogue.

Dvořák began composing his violin concerto in 1879 while spending the summer in Sychrov. Two years earlier he had left his poorly paid position as the organist at the Church of Saint Adalbert in Prague’s New Town, and now he was devoting himself solely to composing. The repeated awarding of a state stipend in support of artists made it easier for him to take that step, and it also led to his friendship with Johannes Brahms, who in turn facilitated Dvořák’s contract with Simrock, which was of vital importance to him. By the end of the 1870s, Dvořák had established himself at home and abroad. However, the path to the definitive version of the violin concerto was not easy: Dvořák’s consultations with Joachim dragged on (the composer waited more than two between the spring of 1880 and the autumn of 1882 year for Joachim’s reaction), and the publisher also had conditions through his advisor Robert Keller. Paradoxically, as it turned out, Joachim, who was supposed to have been the first interpreter of the work, and who made changes in particular to the form taken by the solo part, probably never played Dvořák’s Violin Concerto in public. František Ondříček gave the premiere in October 1883, and after the successful Prague performance with the orchestra of the National Theatre, he also introduced the composition to the enthusiastic Viennese public that December with the Vienna Philharmonic and with Hans Richter on the conductor’s podium. Ondříček then continued to promote the Violin Concerto in A minor throughout his stellar career.

Dvořák went about integrating the orchestra with the solo part similarly to his great model Brahms, whose Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, dates from about the same time. Brahms also dedicated his concerto to Joachim, who premiered it in January 1879. In both cases, the strongly contoured orchestral sound is combined with a solo violin part that is technically difficult, but also richly expressive. Dvořák displays mastery of orchestration, warmth of melodic writing, and vigorous rhythm. The first movement (Allegro ma non troppo) is in an ambiguous sonata form without a recapitulation, and it is linked directly to the lyrical slow movement (Adagio ma non troppo); this smooth attacca transition was one of the points under discussion during the revisions. The Adagio is in ternary form with variations, and its mood is highlighted by the “pastoral” key of F major. The energetic third movement (Finale. Allegro giososo, ma non troppo) employs the rhythm of the furiant, a Czech folk dance, with a melancholy dumka providing contrast in the middle section.

Johannes Brahms

Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 15

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) wrote his monumental Piano Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 15, over the course of five years beginning in 1854. Not long beforehand, in the autumn of 1853, the twenty-year-old Brahms had been introduced in Düsseldorf to Robert and Clara Schumann, and they became his close friends and mentors. In an article in the journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Schumann characterised the young composer and pianist from Hamburg as a very promising and special talent and brought him to the attention of the German musical scene. Brahms’s first compositions appeared in print at the turn of 1853/54. All seemed clear on the horizon: the musician was in contact with such important figures as Joseph Joachim, the baritone Julius Stockhausen, and the composer and pianist Franz Liszt, and he already had a number of compositions to his credit, mainly consisting of chamber and vocal works. However, Robert Schumann attempted suicide in February 1854, and he was confined in a sanatorium in Endenich, leaving his wife Clara alone with their six children (and a seventh on the way). Brahms’s friendship was an important source of support for Clara, and history tells us that they remained friends until Clara’s death in 1896. Under those tense circumstances, Brahms was composing a sonata for two pianos, then after a few months he began giving it a symphonic form. Ultimately, he reworked the first movement of the sonata into the first movement the piano concerto he was creating.

Johannes Brahms was a superb pianist, and already by the 1850s he was giving public performances with both of Beethoven’s last two piano concertos on the programme: G major (No. 4, Op. 58) and E flat major (No. 5, Op. 73, “Emperor”). It is no wonder that Beethoven’s influence is mentioned in connection with Brahms’s Opus 15; in terms of length, Brahms’s concerto even exceeds the dimension of the Emperor Concerto. It was Brahms’s first major orchestral work, and perhaps for that reason it had a lengthy gestation period, during which the composer consulted with others about the orchestration. The premiere took place in early 1859 in Hannover under the baton of Joseph Joachim with the composer himself as the soloist, but the reaction of the audience and critics was lukewarm, and the response to the next performance in Leipzig was even more critical. The work was faulted for resembling more of a symphony with piano obligato than a concerto, from which one would expect virtuosic effects and soloistic exhibition. The Piano Concerto in D minor was only understood later, when it became a model of the new conception of the roles of the piano and orchestra as equal partners. It was first heard in Prague in 1877 in a performance by Karel Slavkovský.

The first movement (Maestoso) in sonata form fully lives up to its tempo marking: the orchestral exposition is already heroic in character. The piano then enters with a melancholy theme, and that contrast permeates the entire movement. The second movement (Adagio) is in the parallel key of D major, and in a letter, Brahms called it “a tender portrait of Clara”. In the autograph, the words “Benedictus, qui venit in nomine Domini” appear beneath the opening bars, leading to the hypothesis that the music in question, like the second movement of the original sonata for two pianos, had been intended as musical material for A German Requiem. The virtuosic third movement (Rondo. Allegro non troppo) takes us to the grand conclusion. In his concerto, Brahms anticipated the further development of the genre, furthering the integration of the piano and orchestra and combining elements of the Baroque concerto grosso and techniques typical of chamber music with a distinctly symphonic vocabulary. The concerto embodies the deep emotions of a 25-year-old composer confronted with the realities of life, yet at the same time it exhibits remarkable maturity in its combination of romantic expression with classical structure.