1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • London

For its second London concert, the Czech Philharmonic is reunited with the Labèque sisters for the Concerto for Two Pianos by Mozart whose music fits them like a glove. For the second half, Chief Conductor Semyon Bychkov leads the Czech Philharmonic in the music of Mahler – the Fifth Symphony - whose symphonies they have been recording together for the last couple of years.

Programme

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Concerto No. 10 in E flat major for two pianos and orchestra, K 365

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor

Performers

Katia and Marielle Labèque pianos

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

To purchase online, visit the event presenter's website.

Performers

Katia & Marielle Labèque pianos

From the Basque region of France, then almost untouched by classical music, to the greatest concert halls in the world – this is the story of the Labèque sisters with a career spanning more than 50 years, who have been described as “the best piano duo in front of an audience today” (New York Times). But the shared story of the sisters, who have had a lifelong and intense relationship both professionally and personally, is much longer. The elder Katia first began playing piano under the tutelage of her mother, a pianist and piano teacher, and two years younger Marielle soon followed suit. In 1968, they entered the Paris Conservatory, but still as two soloists – the idea of forming a piano duo did not arise until after they had graduated from the conservatory, and so they then enrolled in a chamber music class there. They still remember how, while rehearsing Visions de l’Amen, they were suddenly interrupted by Olivier Messiaen, who happened to be passing by their class and wondered who was playing his piece. He was so impressed that he helped them record the work, which was not only their first recording experience but also an important invitation to the world of contemporary composers – after Messiaen, they worked with György Ligeti, Pierre Boulez and Luciano Berio. Their career breakthrough came with their original arrangement of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, which became one of the first gold records of classical music.

The Labèque sisters have performed in famous concert halls from the Musikverein in Vienna to Carnegie Hall in New York, have been guests at major festivals (BBC Proms, Salzburg, Tanglewood) and have appeared with the most celebrated orchestras in the world (Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, La Scala Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, etc.). “We don’t have the huge repertoire of a solo pianist or a violinist, but we have all the more freedom to create our own music and our own projects,” say the sisters, who collaborate with Baroque music ensembles (such as The English Baroque Soloists with Sir John Eliot Gardiner and Il Giardino Armonico with Giovanni Antonini), but they also venture into the field of “non-artificial” (natural) music (Katia even played in a rock band).

The problem of the limited repertoire for piano duo is also solved by addressing contemporary composers. In addition to the above mentioned, in 2015 they gave the world premiere of Philip Glass’s Double Concerto with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Gustavo Dudamel. Two years later they premiered Bryce Dessner’s Concerto for Two Pianos expressly written for them, and recorded it for the album “El Chan”. The Labèques also performed this piece in Prague’s Rudolfinum – although due to the pandemic (2021) without an audience, only in a streamed version. However, this was not the Labèque sisters’ first meeting with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra (whose chief conductor Semyon Bychkov is Marielle Labèque’s husband). In April 2017, the Dvořák Hall witnessed their performance of Poulenc’s Concerto for Two Pianos, and a year later they made their solo debut there.

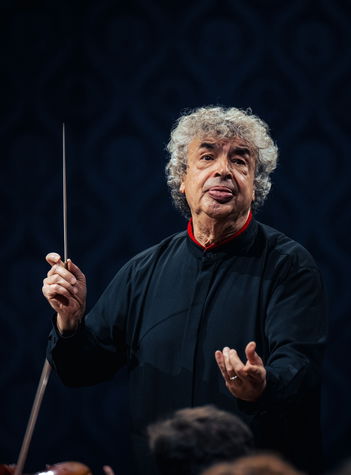

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Concerto No. 10 in E Flat Major for two pianos and orchestra, K 365

Few people had as strong an influence on the young Mozart as his older sister Marie Anna. Known at home as Nannerl, she was Wolfgang’s childhood playmate and a confidante to whom he addressed letters from his travels. Besides extraordinary musical talent, the brother and sister also shared the enjoyment of piquant wordplay. Wolfgang held his sister in deep admiration from an early age, learning from Nannerl and sharing his musical ideas with her. Nannerl was a talented pianist, and she made appearances together with her brother both at home in Salzburg and on tours around Europe, but she was forced to cease appearing in public when she reached adulthood; a career as a professional musician was entirely unthinkable for a young woman in those days.

Piano concertos are a common thread running throughout Mozart’s lifetime. In all, he wrote 27 of them, the first when he was 11 years old, and the last just a few weeks before his death. All his life, he worked to achieve perfect mastery of the form, and there is no doubt that his concertos represent one of the highpoints of the genre’s development. Especially in his late works, perfect formal mastery is wed to his practically inexhaustible melodic inventiveness. Moreover, Mozart premiered most of his concertos himself, so he did not hold back in them in terms of either expression or virtuosity.

The Concerto No. 10 in E flat major for two pianos fits perfectly within Mozart’s series of piano concertos. In 1779 while still employed at the court of the archbishop in Salzburg, he wrote the concerto in order to play it himself with Nannerl. The opening movement bristles with joyous energy, and the two soloists compliment each other in a dialogue that is cheerful and light in some places, majestic in others, with richly colourful interjections from the orchestra. The slow and lyrical second movement features a songful melody, and the tender chords of the two pianos are accompanied by the strings and woodwinds. The concluding rondo overflows with virtuosic motifs and themes played successively by the two soloists and the orchestra. The music comes across as a tongue-in-cheek representation of playful sibling rivalry.

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 5 in C Sharp Minor

The works of Gustav Mahler are inseparable from his relationship with nature. He needed nature and sought it out, expecting it to provide him with “the basic themes and rhythms of his art”, and he compared himself with a musical instrument played by “the spirit of the world, the source of all being.” Just by looking at photographs of the places where he drew energy for composing, we can hardly avoid the impression that there is an intrinsic link between those natural surroundings and the composer’s music. Practical reasons also played a part; Mahler the conductor, always more than 100% devoted his work, could only find the peace and concentration he needed for composing during the summer holiday.

The composer began writing his Fifth Symphony in the summer of 1901 in the Austrian village Maiernigg beside Lake Wörth (Wörthersee), where he had a villa built along with a “hermit’s hut” for composing. By then, he was already in his fifth year at the helm of one of Europe’s most prestigious cultural institutions, the Court Opera in Vienna. This time, however, besides rest, he also needed to recover his health; in February he had nearly died of severe hemorrhoidal bleeding, and his life was saved by a prompt surgical procedure: “As I wavered at the boundary between life and death, I was wondering whether it wouldn’t be better to be done with it right away because everyone ends up there eventually”, he wrote later on.

Death seems to have been at Mahler’s heels from his childhood—seven of his twelve younger siblings did not live to the age of two, his brother Ernst died at age 13, and in 1895 Otto committed suicide at the age of 21. Four years later, the composer buried both of his parents and his younger sister Poldi. Thus, we are not surprised by the unusual number of funeral marches in his works, nor is this the first time that entirely contrasting music came into being in an idyllic environment: the last song of the collection The Youth’s Magic Horn titled The Drummer Boy, three of his Kindertotenlieder, four more songs to texts by Rückert, and the first two movements of a new symphony. “Their content is terribly sad, and I suffered greatly having to write them; I also suffer at the thought that the world shall have to listen to them one day”, he told his devoted friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner (1858–1921). About his symphony, he further noted that it would be “in accordance with all rules, in four movements, each being independent and self-contained, held together only by a similar mood.” Bach’s counterpoint became another important source of inspiration: “Bach contains all of life in its embryonic forms, united as the world is in God. There exists no mightier counterpoint”, he declared; he was spending up to several hours a day studying polyphony.

Suddenly, however, the composer’s life faced a disruption on a cosmic scale. Who knows how the symphony might have turned out if on 7 November 1901 he had not made the acquaintance of an enchanting, musically talented, and undoubtedly very charismatic woman named Alma Schindler (1879–1964) at a friendly gathering. She instantly won over Gustav with her directness, and she wrote in her diary: “That fellow is made of pure oxygen. Whoever gets close to him will burn up.” They were betrothed in December, Alma became pregnant in January, and the wedding took place on 9 March 1902 at Vienna’s Karlskirche in the presence of a small group of family and friends. The couple then embarked on a happy yet complicated period of their lives…

That summer in Maiernigg, Mahler composed the song Liebst du um Schönheit (If you love for beauty) for his wife, and he inserted into his Fifth Symphony one of his most intense and popular slow movements, the Adagietto. The symphony’s premiere took place on 18 October 1904 in Cologne under the composer’s baton. Audience members whistled at the concert to show their disapproval, and as an example of one of the many negative reviews, we can quote Hermann Kipper, according to whom the first movement was too long and the second movement contained many “unmusical” passages full of “appalling cacophony”; according to him, the composer’s brain “finds itself in a constant state of confusion.” After the premiere, Mahler commented laconically: “No one understood it. I wish I could conduct the premiere 50 years after my death.” The symphony was again unsuccessful the following year at performances in Dresden, Berlin, and Prague, where it was played on 2 March 1905 by the orchestra of the New German Theatre (now the State Opera) led by the composer and conductor Leo Blech (1871–1958). The symphony got its first truly warm reception on American soil on 24 March 1905, when Frank Van der Stucken conducted the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Performances followed in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, making Mahler’s music increasingly familiar in American circles before the composer himself came there in 1907.

Within the composer’s oeuvre, the Fifth Symphony represents a turning point. Although there continue to be thematic connections with his songs, we no longer find a vocal component in Mahler’s orchestral works with the exceptions of the Eighth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde. Part I of the approximately 60-minute work consists of two dark, gloomy movements. First, we hear the famous trumpet fanfare announcing death and ushering in a funeral march. The calm, slow motion illuminated by the woodwinds playing a theme in the major mode is disrupted by a wildly dramatic section. Heaviness and dense orchestral sound alternate with introspective passages that reflect upon feelings of loss. The music extinguishes itself nearly in a state of despair, whereupon the next movement breaks forth vehemently (Moving stormily), in which a cantabile theme later appears, accompanied by sobbing winds. The two main ideas are later merged into a triumphant stream of brass, but once again the music leads us back into a state of tense anxiety.

Part II of the symphony consists Mahler’s vast Scherzo. Despite the music’s dance-like character and the absence of the composer’s usual irony, shadows of sadness, again entrusted to the winds, flit past us in this movement as well. Part III of the symphony opens with the intimate Adagietto for strings, made especially famous by Luchino Visconti’s film Death in Venice. The soothing music seems to disperse any the clouds of distress. Then in the bucolic, unrestrained finale, the composer broadly develops several themes, the third of which then leads to a magnificent brass chorale.