1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Simon Rattle

Even world-famous conductors have dreams. Simon Rattle for example has dreamt of conducting the Czech Philharmonic in Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass since it first bewitched him as a young man when he heard the orchestra’s Supraphon recording with Karel Ančerl. This sacred work will be preceded by the second set of Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances. These, together with the first set, will be recorded for future release on PENTATONE.

Programme

Antonín Dvořák

Slavonic Dances, Op. 72 (35')

— Intermission —

Leoš Janáček

Glagolitic Mass, cantata for solo voices, mixed choir, orchestra, and organ (45')

Performers

Iwona Sobotka soprano

Lucie Hilscherová alto

Pavel Černoch tenor

Jan Martiník bass

Petr Čech organ

Prague Philharmonic Choir

Lukáš Vasilek choirmaster

Simon Rattle conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Whenever you need to purchase a wheelchair-accessible ticket.

The older Janáček got, the more modern his compositions became. His music finally began to receive acclaim after the Prague premiere of Jenůfa in 1916 when he was already over 60. During his years of waiting for recognition, he cast aside conventions and sought to refine his unique musical language to its very essence.

The Glagolitic Mass is one of the most powerful sacred works in music history. In 1926, aged 72, Janáček set about writing music to the Old Church Slavonic text. Once his creative zeal had been ignited, he composed quickly and incredibly, sketched out the entire work in just three weeks. He continued to make substantial changes to the Mass even after its premiere on 5 December 1927 in Brno up until his death half a year later.

In a review of the premiere performance, the musicologist Ludvík Kundera called the composer an old man and a firm believer. Janáček’s often quoted retort - “No old man, no believer! Young fellow!” – must not be taken at face value as he was indisputably a spiritual person. Raised in a Benedictine monastery in the Old Brno district, he taught his children faith and prayer. Yet, during his lifetime, he clearly distanced himself from the Catholic Church and this may be why he chose to set the non-denominational Old Church Slavonic text of the mass to music.

Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances were born from words of encouragement which Janáček, on the other hand, did not very often get to hear. Because of the commercial success of Antonín Dvořák’s Moravian Duets, the Berlin publisher Fritz Simrock asked Dvořák for “something in the manner of Brahms’s Hungarian Dances”. Dvořák reacted to this suggestion on 24 March 1878 by sending Brahms this message:

“Most honoured master! I have been entrusted with writing some Slavic dances for Mr Simrock. Not knowing how to begin, I tried to lay my hands on your famous Hungarian Dances, and I am taking the liberty of using them as a model for preparing the Slavonic Dances in question.”

Following the tremendous success of the first set of dances, Dvořak’s Berlin publisher asked for more. The composer hesitated at first because, in his words, “it’s damned hard to do the same thing twice”. Finally, when he did find inspiration for a second set, like for the first, he composed Slavonic Dances simultaneously for versions for piano four hands and for orchestra.

The second set of Slavonic Dances of 1886 covers a wider area of the Slavic territory than the first, presenting such dances as the odzemek from Moravian Silesia, the Ukrainian dumka, the Polish polonaise, and the Serbian kolo. However, Dvořák never directly quotes folk melodies in any of the dances. What audiences will hear are masterful stylisations resulting in entirely original compositions that are “pure” Dvořák.

Performers

Iwona Sobotka soprano

The Polish soprano Iwona Sobotka is a winner of the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, one of the world’s most prestigious music competitions. Over the last 20 years, she has firmly established herself on concert and opera stages. A graduate of the Chopin University of Music in Warsaw and of the Escuela Superior de Música Reina Sofia in Madrid, she has been heard at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, Paris’s Opéra national, Berlin’s Komische Oper, and Madrid’s Teatro Real.

Her recent roles include Dvořák’s Rusalka. Sir Simon Rattle, with whom she has long been collaborating, has called her “A really unusual musician with a uniquely beautiful sound quality matched with fierce intelligence.” They have appeared together performing both the operatic (Wagner’s Parsifal) and concert repertoire. For example, with the Berlin Philharmonic she shined in Beethoven’s Christ on the Mount of Olives and Ninth Symphony; she has sung the Glagolitic Mass successfully with the Staatskapelle Berlin. She is also famed for performing the Polish vocal repertoire, and in the 2023/24 season, she served as the artist-in-residence for Poland’s Rubinstein Philharmonic.

Lucie Hilscherová alto

The Czech mezzo-soprano Lucie Hilscherová, a laureate of the Karlovy Vary International Competition, Cantilena Bayreuth, and Musica Sacra in Rome, makes guest appearances at many Czech and Slovak theatres including Prague’s National Theatre, and also at the National Theatre in Mannheim, where she has sung roles in a broad repertoire ranging from Mozart to Hába. She introduced herself to the public at Tokyo’s Suntory Hall and London’s Barbican Hall as Háta in The Bartered Bride. She has also appeared around Europe in Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass, which she performed successfully in the spring of 2022 with Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic at the Rudolfinum, on a European tour, and that September on a floating stage on the Vltava.

Her domain is the concert hall, singing both the art song and oratorio repertoire, as is seen from her collaborations with leading orchestras and conductors. She also enjoys performing early music and the works of contemporary composers. She has made festival appearances at Musikfest Stuttgart, Beethovenfest Bonn, and Grafenegg Musik-Sommer, and in past seasons she has starred with the Czech Philharmonic and the Prague Philharmonic Choir as the alto soloist in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on that orchestra’s subscription programmes and at the Prague Spring Festival.

Pavel Černoch tenor

Talent, industriousness, and an intelligent vocal approach have made Pavel Černoch one of today’s most respected and sought-after tenors. Critics highlight the silky tenderness and malleability of his voice and praise his acting talent, thanks to which he has convincingly portrayed such complex operatic characters as Janáček’s Laca, the Prince in Rusalka, and Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca.

His portrayals of roles mainly from the 19th and early 20th centuries have already been heard, for example, at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, the Opéra national in Paris, London’s Covent Garden, and Madrid’s Teatro Real; he has also performed at the BBC Proms and festivals in Bregenz, Salzburg, and Glyndebourne. He has appeared on stage with Sir Simon Rattle in performances including a production of Káťa Kabanová in Berlin

A graduate of the music management programme at the Janáček Academy of Performing Arts in Brno, he also went abroad to pursue his dream of becoming a singer. At the very beginning of his vocal career, he met the teacher Paolo De Napoli, who became his life-long mentor. His path to fame is recorded in the Czech Television documentary Pavel Černoch – Enfant terrible?

Jan Martiník bass

Vocal beauty combined with brilliant technique and comic talent have made Jan Martiník, a graduate of the Janáček Conservatoire and of the University of Ostrava, into one of the leading singers of the younger generation. Despite having just recently celebrated his 30th birthday, he already has several competition successes to his credit (victories at the Antonín Dvořák International Competition in Karlovy Vary and at BBC Cardiff Singer of the World, laureate of the Yelena Obraztsova International Singing Competition in Moscow, finalist at Placido Domingo’s singing competition Operalia). He has made guest appearances at Prague’s National Theatre and has held engagements first at the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava, then at Berlin’s Komische Oper and the Staatsoper Unter den Linden.

He has appeared in concert with such famed orchestras as the Czech Philharmonic (for example in the Glagolitic Mass on a European tour and on a floating stage on the Vltava), the Rotterdam Philharmonic, the Staatskapelle Dresden, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the King’s Consort, and Collegium 1704. He is especially acclaimed in the art song repertoire for the purity of his interpretations of Schubert’s Winterreise and of Dvořák’s Biblical Songs.

Petr Čech organ

Prague Philharmonic Choir

The Prague Philharmonic Choir (PPC), founded in 1935 by the choirmaster Jan Kühn, is the oldest professional mixed choir in the Czech Republic. Their current choirmaster and artistic director is Lukáš Vasilek, and the second choirmaster is Lukáš Kozubík.

The choir has earned the highest acclaim in the oratorio and cantata repertoire, performing with the world’s most famous orchestras. In this country, they collaborate regularly with the Czech Philharmonic and the Prague Philharmonia. They also perform opera as the choir-in-residence of the opera festival in Bregenz, Austria.

Programmes focusing mainly on difficult, lesser-known works of the choral repertoire. For voice students, they are organising the Academy of Choral Singing, and for young children there is a cycle of educational concerts.

The choir has been honoured with the 2018 Classic Prague Award and the 2022 Antonín Dvořák Prize.

Lukáš Vasilek choirmaster

Lukáš Vasilek studied conducting and musicology. Since 2007, he has been the chief choirmaster of the Prague Philharmonic Choir (PPC). Most of his artistic work with the choir consists of rehearsing and performing the a cappella repertoire and preparing the choir to perform in large-scale cantatas, oratorios, and operatic projects, during which he collaborates with world-famous conductors and orchestras (such as the Berlin Philharmonic, the Czech Philharmonic, the Israel Philharmonic, and the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic).

Besides leading the PPC, he also engages in other artistic activities, especially in collaboration with the vocal ensemble Martinů Voices, which he founded in 2010. As a conductor or choirmaster, his name appears on a large number of recordings that the PPC have made for important international labels (Decca Classics, Supraphon); in recent years, he has been devoting himself systematically to the recording of Bohuslav Martinů’s choral music. His recordings have received extraordinary acclaim abroad and have earned honours including awards from the prestigious journals Gramophone, BBC Music Magazine, and Diapason.

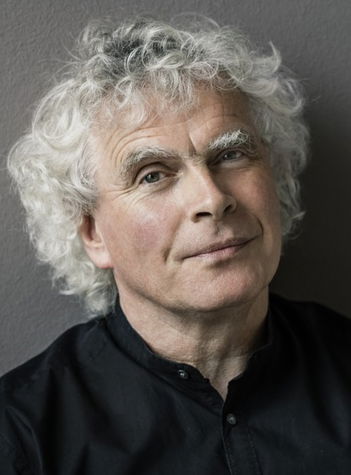

Simon Rattle conductor

We have seen one of today’s most distinguished conductors, Sir Simon Rattle, relatively often at the Rudolfinum in recent years. His long-term cooperation with the Czech Philharmonic has led to his appointment together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, as Artist-in-Residence for the 2022/2023 season. At his appearances with the Czech Philharmonic, he has performed a number of symphonic works and, most notably, compositions for voices and orchestra from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the repertoire for which Rattle has been the most acclaimed. He appeared most recently at the Rudolfinum in February 2024 with the pianist Yuja Wang, with whom he made a Grammy-nominated recording from their joint tour of Asia in 2017. From the 2024/2025 season, he becomes the Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

A native of Liverpool and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music has held a series of important positions in the course of his long career. He came to worldwide attention as the chief conductor of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he was employed for a full 18 years (for eight years as its music director); next came 16 years with the Berlin Philharmonic (2002–2018; artistic director and chief conductor) and six years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He opened the 2023/2024 season as chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with the title of “principle artist”, and he is the founder of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. Besides holding full-time conducting posts, he maintains ties with the world’s leading orchestras and gives concerts frequently in Europe, the USA, and Asia.

He has made more than 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics). He has won a number of prestigious international awards for his recordings including three Grammy Awards for Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which he recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Besides the prizes mentioned above, Rattle’s long-term partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic also led to the new educational programme Zukunft@Bphil, which has achieved great success. Even after moving on from that orchestra, Rattle did not abandon his engagement with music education, and he has taken part together with the London Symphony Orchestra in the creation of the LSO East London Academy. Since 2019, that organisation has been seeking out talented young musicians, developing their potential free of charge regardless of their origins and financial situation.

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Slavonic Dances, Op. 72

It was at the recommendation of Johannes Brahms that in 1878 the Berlin publisher Fritz Simrock printed the cycle of Moravian Duets by Antonín Dvořák. Because of the success of the new work, the publisher commissioned another composition, this time a cycle of dances. Simrock was readily taking advantage of the trendy popularity of folk influences and of the characteristically “exotic” quality exhibited by the melodies and rhythms of various ethnic groups including the Slavs. Dvořák’s Moravian Duets had been published thanks to Johannes Brahms’s recommendation, and Simrock wanted the Czech composer’s new cycle to be “something in the manner of Brahms’s Hungarian Dances”. Dvořák reacted to this suggestion on 24 March 1878, informing Brahms: “Honoured Master! [...] I have been entrusted with writing some Slavonic dances for Mr Simrock, but because I did not know how to begin, I tried to get my hands on your famous Hungarian Dances, and I am taking the liberty of using them as a model for working on corresponding Slavonic Dances.” That same year (1878), he wrote his first series of eight Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, originally intended (like Brahms’s cycle) for piano four-hands. The first series was a huge success, and the Berlin publisher requested a continuation. This time, however, Dvořák hesitated initially: “Doing the same thing twice is damned hard,” he complained to Simrock. In the end, however, he did find inspiration for a second series, which also contains eight dances, and as was the case with the first series, the version for piano four-hands appeared simultaneously with an orchestral version.

Besides Czech dances, the second series of Slavonic Dances, Op. 72 (1886) covers a wider range of Slavic territory, with the dances including the odzemek of Moravian Silesia, the Ukrainian dumka, the Polish polonaise, and the Serbian kolo. Dvořák did not quote folk melodies directly in any of the dances, however. These masterful stylisations of characteristic elements are pure Dvořák and entirely unique, and although the individual dances are identifiable, Dvořák did not assign them titles, providing only tempo indications. Three dances of the second series (nos. 1, 2, and 7) were first heard at a concert on 6 January 1887 at the Rudolfinum under the composer’s baton.

Leoš Janáček

Glagolitic Mass, a cantata for soloists, choir, orchestra and organ

Among great creative figures, Leoš Janáček is remarkable in that the older he got, the more “youthful”, original, and modern the music that he wrote became. This was perhaps because he had lost everything. Released by the cruelty of fate from his ties and concerns for his parents and his children, he was truly able to find himself. He cast aside conventions and tried to get to the heart of things.

Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass is one of the most powerful sacred compositions in music history. The 72-year-old composer wrote the music to the text in Old Church Slavonic in 1926 at his favourite spa, Luhačovice. “The rain in Luhačovice is pouring, just pouring. I look out of the window at the gloomy mountain Komoň. The clouds come rolling in, and the wind tears and scatters them. […] The darkness becomes denser and denser. Now I look out into the black of night; lightning slashes into the darkness.” That is how Janáček described the atmosphere that August, when he began writing his Glagolitic Mass. The decision was made quickly. Although he had taken an interest in the Old Church Slavonic text of the Mass a few years beforehand and had made a few sketches, the music that he ultimately began writing in Luhačovice had nothing in common with those sketches. For Janáček, starting the new work was quite emotional. His ideas had to mature, but once creative fervour had taken hold, he composed quickly. He sketched out the entire Mass in just three weeks! By October 1926, he had finished it. He made more quite substantial changes after the premiere, which took place on 5 December 1927 in Brno. Janáček was able to make cuts. He is never verbose; he is precise.

For example, in the movement “Věruju” (Credo) he shortened the orchestral interlude that contained a very powerful passage inducing the atmosphere before the choir begins singing about Christ’s crucifixion. Janáček originally scored this harsh passage for three (!) sets of tympani, and he combined them with expressive music for brass and organ. In a letter to Kamila Stösslová he wrote: “…so I’m doing a bit of a depiction of the legend that when Christ was stretched out on the cross, the heavens were torn. So I wrote rumbling and lightning…” His wife Zdena supposedly told him: “Leoš, that’s impossible; you’re cursing at the Lord God there.” And a while later Janáček said: “So I’ve gotten rid of the tympani there…”

Although the Glagolitic Mass is a musical setting of a liturgical text, the work is not confessional in character. To Ludvík Kundera’s review, in which he called the composer an “old man” and a “firm believer”, Janáček’s reply was “No old man, no believer, you youngster”. This is often quoted, but we must take it with a grain of salt. Janáček was unquestionably a spiritual person. He was raised in the environment of the church at the Benedictine Monastery in Old Brno. However, he was not a practicing Catholic. We know only that he brought his children up in faith and prayer. He apparently felt distanced from the Catholic Church, so he was attracted to the idea of writing a Mass, but to the Old Church Slavonic text.