1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Jiří Vodička

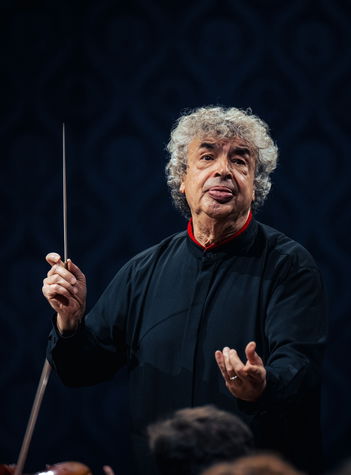

The Czech Philharmonic presents Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony with its Chief Conductor Semyon Bychkov who is internationally acclaimed for his interpretations of the Russian composer’s music. Written in the second half of the 1930s during Stalin’s purges in the Soviet Union, the Symphony earnt Shostakovich a half-hour standing ovation. Today it is regarded as one of the pinnacles of modern music.

Programme

Dmitri Shostakovich

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 (30')

— Intermission —

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 (44')

Performers

Jiří Vodička violin

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

“Before the war there probably wasn’t a single family who hadn’t lost someone, a father, a brother, or if not a relative, then a close friend. Everyone had someone to cry over, but you had to cry silently, under the blanket, so no one would see. Everyone feared everyone else, and the sorrow oppressed and suffocated us. It suffocated me too. I had to write about it.” — Dmitri Shostakovich

On 21 November 1937 in Soviet Leningrad, Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D minor was heard for the first time. The atmosphere in the hall was tense, and not just because of the societal expectations that came with the premiere of a major symphonic work by a famous composer in those days. Everyone in attendance knew that nothing by the composer had been heard in public for two years because his music had displeased Stalin.

During the Great Terror, Shostakovich’s life hung in the balance, and many of his acquaintances, friends, and even relatives lost their lives. In Shostakovich’s instance, however, Stalin was aware that the composer was world famous and that his music was played in the most prestigious concert halls internationally. Stalin therefore did not want to destroy him but instead to change him or tame him. Whether Shostakovich let himself be tamed is up to the listeners to decide.

Since the Romantic era, classical music has been celebrated for its ability to encapsulate different moods, often including the most extreme. Dmitri Shostakovich further enriched that range with his notorious irony. He was also a composer who thought polyphonically, juxtaposing musical ideas in sharp and often unexpected contrasts. Moreover, seldom in his music are emotions or moods depicted unambiguously. Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony stands out for all these reasons. In the dark and dramatic first movement, there are flashes of lyricism and tenderness. A joyous smile is frozen on the lips of the satirical dance which proceeds it. The sorrowful and quiet Largo of the third movement is interrupted by heartrending cries of suffering, and in the frantic finale, festive optimism becomes strained and turgid.

Presented alongside the Fifth Symphony will be Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto in A minor performed by the Czech Philharmonic’s Concertmaster Jiří Vodička. Written in 1947-48 when all music was subject to censorship under the Zhdanov Doctrine, the concerto was deemed an ideologically problematic work and could not be performed publicly for several years. The great violinist David Oistrakh finally gave the concerto its very successful premiere in 1955 in Leningrad, and since then the work has been celebrated worldwide.

Performers

Jiří Vodička violin

One of the most important and sought-after Czech violinists and the concertmaster of the Czech Philharmonic Jiří Vodička has excelled in a number of competitions since very early on (Kocian International Violin Competition, Prague Junior Note, the best participant at violin classes led by Václav Hudeček, among others). At the unusually early age of 14, he was admitted to the Institute for Artistic Studies at the University of Ostrava, where he studied under the renowned pedagogue Zdeněk Gola. He graduated in 2007 with a master’s degree. His success continued as an adult, for example winning first and second prizes at the world-famous competition Young Concert Artists (2008) held in Leipzig and New York.

He has made solo appearances not only with Czech orchestras like the Prague Philharmonia or the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra, but also with the Qatar Philharmonic Orchestra, the New Philharmonic Orchestra of Westphalia, and the Wuhan Philharmonic Orchestra. His professional activities are of greater breadth, however. In 2014, he recorded his debut solo album “Violino Solo” on the Supraphon label, and crossover fans can hear him on his worldwide Vivaldianno tour. He has performed chamber music with the outstanding Czech pianists Martin Kasík, Ivo Kahánek, Ivan Klánský, David Mareček, and Miroslav Sekera. He regularly takes part at famous festivals, such as the Prague Spring, Janacek’s May, Grand festival of China and Choriner Musiksommer. He was a member of the Smetana Trio from 2012 to 2018; in 2020 he founded the Piano Trio of the Czech Philharmonic, with which he won the Vienna International Competition in 2021. Many of the concerts of the “Czech Paganini”, as Vodička is sometimes called because of his extraordinary technical skill, have been recorded by Czech Television, Czech Radio, or the German broadcasting company ARD. Besides all of that he teaches at the University of Ostrava.

He plays Italian violin made by Joseph Gagliano in 1767 which he received for long-term use from the Czech Philharmonic’s former chief conductor Jiří Bělohlávek.

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Dmitri Shostakovich

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77

Dmitri Shostakovich composed his First Violin Concerto in 1948, and the inspiration for the work is said to have come to him in Prague. Shostakovich had been invited to the Prague Spring Festival in 1947 (26 May) to perform some of his compositions including the Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor; in an ensemble put together for the special occasion, Shostakovich appeared as the pianist, David Oistrakh played the violin part, and Miloš Sádlo played the cello. Shostakovich had known Oistrakh personally since the middle of the 1930s, when they were members of a Soviet delegation sent to establish cultural ties with Turkey, but this was their first appearance together on stage. Under the impression of Oistrakh’s artistry, Shostakovich wrote his Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 soon after the Prague concert. The composer said the work was more of a symphony than a concerto in the true sense of the word, and Oistrakh confirmed that it makes extraordinary technical, intellectual, and emotional demands on the soloist. The work had to wait a long time for its premiere. Shostakovich was aware that during the era of the artistic policy of Socialist Realism, there was no hope of a favourable reception for his “formalist” music, so he saved this work along with several others for more favourable times. It was not until after Stalin’s death that the atmosphere relaxed somewhat. The premiere took place on 29 October 1955 in the Great Hall of the Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) Philharmonic with Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting, and the concerto won the spontaneous acclaim of the public. The work was ignored by officialdom, however, but that was more of a source of satisfaction for Shostakovich. For its belated premiere, the work was designated as Opus 99 as an alibi to hide the delay since the work’s creation (Opus 99 actually belongs to music for the 1956 film The First Echelon).

The first movement (Nocturne) begins in the low strings, then the music rises to higher spheres as more string join in along with the bell-like sound of celesta and harp. Dark, even aggressive tones then break into this transparent texture. The development and recapitulation sections are proportionally briefer, but the sonata layout is clear. In terms of its character and length, the Nocturne amounts to an introduction to the second movement, a ternary scherzo. The third movement (Passacaglia) is one of the many examples of Shostakovich’s mastery of contrapuntal forms; the composer also left room for a solo cadenza that creates the link to the final movement (Burlesque). Predominant in the movement is the grotesquely sarcastic tone for which Shostakovich’s symphonic works are often compared to the music of Gustav Mahler.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s life was a constant struggle with government ideology. In 1936, after the premiere of the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, he became a target of fierce criticism based on Stalinist aesthetics, which demanded comprehensible, pleasant music that was accessible to the working class. Similar attacks were repeated later, but on the other hand the composer received honours and accepted official positions. The Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47, dates from a period when political purges had cost Shostakovich a number of friends, some of whom were imprisoned while other disappeared mysteriously or were even tortured to death. The composition is one of Shostakovich’s first compromises, although his compromises merely affirm the enormous creative potential by which he was able to maintain at least a stalemate in his chess game with dogmatic officials, while never stooping to write music of inferior quality and standing up to all of the pressure both as an artist and as a man.

The Fifth Symphony was composed from April to July 1937. In terms of its character, the work reveals Gustav Mahler (mentioned above) as Shostakovich’s great model. To avoid accusations of “formalism”, Shostakovich published the composition’s programmatic intentions: he described the first movement as heroic tragedy, the scherzo as an expression of the joy of life, the slow movement as a meditation, and the finale as expressing the achieving of victory. Basically, the programme amounts to a poetic expression of the usual “content” of a symphonic cycle. Such an explanation was sufficient for the observers from the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians. Critics heard Slavic melodic elements in the music, and that was credited to the work’s favour. Nonetheless, the composer did not give up the use of chromaticism and dissonances; in fact, the second theme of the first movement is constructed from a selection of material that approaches the principle of dodecaphony. Music is an abstract artform, and Shostakovich succeeded at creating the impression of joy where he was expressing defiance; he later said it was certainly clear to everyone that the joy of the second movement was under compulsion, as if someone had commanded: “Rejoice!” According to another interpretation, he was parodying the official Communist Party banquets he was forced to attend. His biographers call the first movement “Faustian”. It uses some of the motifs of the Fourth Symphony, which the composer withdrew just before its performance, being aware that after the criticism of the opera Lady Macbeth, the work would be regarded as a provocation (the Fourth Symphony was not performed until 1961); for him personally, carrying material over into the new composition was one of his ways of resisting. The movement is derived from a four-note motif that is transposed into a variety of positions, and the music transforms itself into an energetic march that forms the climax of the movement. The frequent rhythmic shifts of the parodic waltz of the second movement constantly bring new surprises, and it is in that movement and in the Largo third movement that the composition’s Mahlerian model is most evident. By contrast, the finale is compared to the legacy of Tchaikovsky because of its structure and its emotional ending, and the performing of Tchaikovsky’s dramatic overture Romeo and Juliet on the first half of the programme at the premiere of the Fifth Symphony on 21 November 1937 in Leningrad underscores the mutual resemblance.

Yevgeny Mravinsky also conducted the premiere of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony. As Shostakovich recalled: “The atmosphere was tense, nervous. [...] The situation was critical, and not just for me. Which way did the wind happen to be blowing? [...] I felt like a gladiator in Giovagnoli’s novel Spartacus, or like a fish cooking on a frying pan...” Shostakovich’s defiance combined with well disguised ridicule aimed at the ideologue’s directives turned out to be a success, however. Shostakovich had learned to balance on a tightrope over the abyss, and the public understood it. Yevgeny Mravinsky also conducted the Czech Philharmonic in a performance of the Fifth Symphony at the inaugural Prague Spring Festival in 1946.