1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Tokyo

The final concert of the residency “festival” at Suntory Hall featuring the great symphonies and concertos of Antonín Dvořák will present the Violin Concerto played by the American virtuoso Gil Shaham and the great New World Symphony.

Programme

Antonín Dvořák

In Nature’s Realm, concert overture, Op. 91

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 “From the New World”

Performers

Gil Shaham violin

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

To purchase online, visit the event presenter's website.

Performers

Gil Shaham violin

“I was at school. There was a knock on the door and a message: ‘Gil, can you come down to the principal’s office?’ That can’t be a good thing…am I in trouble? And London Symphony Orchestra representatives are there, looking for a violinist ready with the repertoire to stand in for Itzhak Perlman. I had to choose whether to go back to class or to board the Concorde with them and fly to London immediately. Thousands of metres above the ground, champagne on board, and an unprecedented reception! It took me just a few seconds to decide. They were overjoyed, and we took off,” says the now world-famous violinist Gil Shaham, recalling the watershed moment of his musical career. He was 18 years old, and although he had already achieved many successes by then—he made his debut with the Israel Philharmonic at age ten and a year later won the Claremont Competition in Israel, where he was staying with his parents at the time—he was still a “mere” student at New York’s Juilliard School.

Then the offer to stand in for Itzhak Perlman arrived. Thanks to Shaham’s great success at that concert with the London Symphony Orchestra led by Michael Tilson Thomas, invitations started pouring in for concerts and recordings; suddenly, his name was appearing in all the most important musical media. To this day, he thrills audiences at the world’s most famous concert halls with perfect technique supported by masterful musicianship and very amiable stage presence, as Svatava Barančicová writes for the OperaPlus portal: “His breathtaking virtuosity knows no bounds, yet on stage he makes a most delicate, modest impression. He is always smiling at the public and the orchestra players, and he connects with the musicians, following their playing and enjoying their passages just as he does his own. He does not tower over the orchestra in the pose of a virtuoso; he just puts his fingers on the fingerboard and fully demonstrates his exceptional skills: shocking speed, smooth execution of technically difficult figures that lie awkwardly for the violin, and upward leaps that slash through thickets of notes like the cold, precise flash of a steel blade. His double stops are perfectly in tune at any tempo and in every register. And he smiles disarmingly while doing all of this.”

The review is of a concert at last year’s Dvořák Prague Festival, when Gil Shaham appeared with the Israel Philharmonic. He has been a frequent guest in Prague, however: the Dvořák Prague Festival welcomed him back in 2016 with Antonio Pappano, then three years later he performed brilliantly with the Prague Philharmonia in Dvořák’s Violin Concerto, which he is playing this time in New York with the Czech Philharmonic. “I love Dvořák!” Shaham declares, adding that he listened to the composer’s symphonies already in his youth.

Shaham’s repertoire is large, of course. A few years ago he released a very successful recording of Johann Sebastian Bach’s complete solo sonatas and partitas, and besides traditional works of the classical and romantic eras, he also focuses on playing violin concertos of the 20th century. That is the direction his recording activities have taken in recent years, and one CD from the series “1930s Violin Concertos” was nominated for a Grammy. However, he already has a Grammy to his credit for the album American Scenes, which he recorded at age 27 with André Previn, and he has received many other important musical awards such as the Grand Prix du Disque, the Diapason d’Or, and the designation as Editor’s Choice from the magazine Gramophone.

At the Rudolfinum and around the world, audiences can see Shaham playing his rare “Countess Polignac” Stradivarius. He collaborates regularly with the Berlin Philharmonic, the Orchestre de Paris, the New York Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. However, he enjoys being at home in New York, where he has been living for many years with his wife, the violinist Adele Anthony, and their three children.

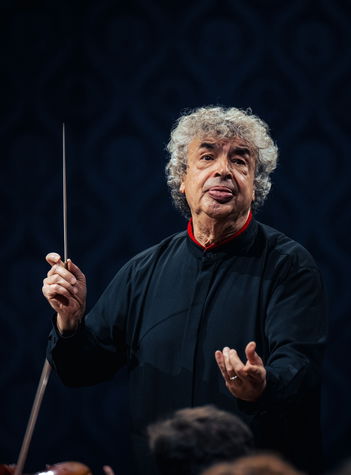

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

In Nature’s Realm, concert overture, Op. 91

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53

Personal relationships, friendships, and mutual respect among individuals leave a more tangible imprint on history than one might expect. An illustrative chapter of music history involved Fritz Simrock, Antonín Dvořák, Johannes Brahms, Robert and Clara Schumann, and Joseph Joachim.

Among the compositions for solo instrument and orchestra by Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904), three concertos stand out: the Piano Concerto in G minor (Op. 33), the Violin Concerto in A minor (Op. 53), and the Cello Concerto in B minor (Op. 104). The first two date from almost the same period and were both actually published in 1883, but they underwent a different genesis. While Dvořák apparently came up with the idea of composing the early version of the piano concerto in 1876 on his own, perhaps fondly imagining Karel Slavkovský at the piano, the stimulus for writing the Violin Concerto in A minor was external. The publisher Simrock commissioned the increasingly popular Czech composer to write another composition of “Slavonic” character. The Czech Suite, Op. 39, the Slavonic Rhapsodies, Op. 45, the Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, and the String Quartet in E flat major, Op. 51 were all earlier works by Dvořák that were popular items on the sheet music market and were influenced by the melodic and rhythmic patterns of the folk music of the Czechs, Moravians, and other Slavic peoples. The violin virtuoso, conductor, and director of the Hochschule für ausübende Tonkunst Joseph Joachim, whom the composer had met in early April 1879 in Berlin, also supported the idea of a new concerto. The concerto’s dedication to Joachim shows Dvořák’s regard for the chance to collaborate with the legendary violinist and pedagogue.

Dvořák began composing his violin concerto in 1879 while spending the summer in Sychrov. Two years earlier he had left his poorly paid position as the organist at the Church of Saint Adalbert in Prague’s New Town, and now he was devoting himself solely to composing. The repeated awarding of a state stipend in support of artists made it easier for him to take that step, and it also led to his friendship with Johannes Brahms, who in turn facilitated Dvořák’s contract with Simrock, which was of vital importance to him. By the end of the 1870s, Dvořák had established himself at home and abroad. However, the path to the definitive version of the violin concerto was not easy: Dvořák’s consultations with Joachim dragged on (the composer waited more than two between the spring of 1880 and the autumn of 1882 year for Joachim’s reaction), and the publisher also had conditions through his advisor Robert Keller. Paradoxically, as it turned out, Joachim, who was supposed to have been the first interpreter of the work, and who made changes in particular to the form taken by the solo part, probably never played Dvořák’s Violin Concerto in public. František Ondříček gave the premiere in October 1883, and after the successful Prague performance with the orchestra of the National Theatre, he also introduced the composition to the enthusiastic Viennese public that December with the Vienna Philharmonic and with Hans Richter on the conductor’s podium. Ondříček then continued to promote the Violin Concerto in A minor throughout his stellar career.

Dvořák went about integrating the orchestra with the solo part similarly to his great model Brahms, whose Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, dates from about the same time. Brahms also dedicated his concerto to Joachim, who premiered it in January 1879. In both cases, the strongly contoured orchestral sound is combined with a solo violin part that is technically difficult, but also richly expressive. Dvořák displays mastery of orchestration, warmth of melodic writing, and vigorous rhythm. The first movement (Allegro ma non troppo) is in an ambiguous sonata form without a recapitulation, and it is linked directly to the lyrical slow movement (Adagio ma non troppo); this smooth attacca transition was one of the points under discussion during the revisions. The Adagio is in ternary form with variations, and its mood is highlighted by the “pastoral” key of F major. The energetic third movement (Finale. Allegro giososo, ma non troppo) employs the rhythm of the furiant, a Czech folk dance, with a melancholy dumka providing contrast in the middle section.

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”

Dvořák’s prestigious invitation to New York did not come out of nowhere. For years, his music had already been familiar in the United States, and American newspapers had been writing about his successes in Europe as a composer and conductor. Above all, however, for America Dvořák was iconic as a national composer. “Americans expect great things from me, and above all, supposedly, that I will show them the way to the promised land and to the realm of new, independent art, in short, how to create the music of a nation!! […] Certainly, this is an equally great and beautiful task for me, and I hope I shall have the good fortune to succeed with God’s help. There is more than enough material here,” wrote the composer to his friend Josef Hlávek after arriving in America. Dvořák did, in fact, delve into America’s musical material with great interest, as is revealed in an interview for the New York Herald: “Since I have been in this country I have been deeply interested in the national music of the negroes and the Indians. […] I intend to do all in my power to call attention to this splendid treasure of melody which you have.” Dvořák did not borrow the melodies, however. He created his own melodies using many of the characteristic features of folk songs that he combined with the essence of American folklore. In addition, the motifs from the new Symphony in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”, did not come into the world instantly in the form in which we now know them. This is documented by the composer’s sketches, in which the now famous themes appear still with many deviations from the final version. It is clear that during the compositional process, Dvořák was giving ever deeper expression to the “American spirit” that he wanted the music to embody, adding syncopations including a special rhythm known as the “Scotch snap”, highlighting the pentatonic scale etc. However, his new symphony was by no means an attempt to do everything differently from his previous symphonies. As he was finishing the score, he brought this up in a letter to his friend Göbl: “I’m just now finishing my Symphony in E minor, which will be strikingly different from my earlier ones, mostly in terms of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic figures—just my orchestration has not changed, something in which I probably will not advance any further, nor do I wish to, and I have my reasons.”

The composer also mentioned the work’s tempestuous reception at the premiere at New York’s Carnegie Hall in December 1893 (Anton Seidl conducted the New York Philharmonic) in a letter to his publisher Fritz Simrock in Berlin: “The symphony’s success on December 15th and 16th was magnificent; the newspapers say that no composer has ever before achieved such a triumph. I was seated in a box, the hall was occupied by New York’s most elite public, and the people applauded so much that I had to wave from my box like a king to show my gratitude! Like Mascagni in Vienna (don’t laugh!). You know that I prefer to try to avoid such ovations, but I had to do this and show myself.” The composer did not inscribe the title “From the New World” on the score’s title page until a few months after finishing the work; it was on the very day that he handed the score over to the conductor for rehearsals. The title of the first work he had written in America gave rise to a great deal of comment in newspaper articles. Having read them, the composer supposedly remarked with a smile: “Well, it seems I have confused their minds a bit.”