1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Yuja Wang

This set of three concerts has some of the season’s biggest stars, bringing together two artists-in-residence of the Czech Philharmonic. Yuja Wang will perform Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto a year after having shined at Carnegie Hall in a marathon of all four Rachmaninoff concertos on one evening.

Programme

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 (39')

— Intermission —

Anton Bruckner

Symphony No. 6 in A major (54')

Performers

Yuja Wang piano

Simon Rattle conductor

Czech Philharmonic

The sale of individual tickets for subscription concerts (orchestral, chamber, educational) will begin on 2 June 2025 at 10 a.m.

Individual tickets for all public dress rehearsals will go on sale on 10 September 2025 at 10 a.m.

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9.00 am to 6.00 pm.

Aftertalk

After the concert on Saturday 10 February we invite you to an aftertalk with conductor Simon Rattle in the Dvořák Hall. The aftertalk will be in English and will be interpreted into Czech.

Moderated by David Mareček

Performers

Yuja Wang piano

Pianist Yuja Wang is celebrated for her charismatic artistry, emotional honesty and captivating stage presence. She has performed with the world’s most venerated conductors, musicians and ensembles, and is renowned not only for her virtuosity, but her spontaneous and lively performances, famously telling the New York Times. “I firmly believe every program should have its own life, and be a representation of how I feel at the moment”. This skill and charisma was recently demonstrated in her performance of Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2 at Carnegie Hall’s Opening Night Gala in October 2021, following its historic 572 days of closure.

Yuja was born into a musical family in Beijing. After childhood piano studies in China, she received advanced training in Canada and at the Curtis Institute of Music under Gary Graffman. Her international breakthrough came in 2007, when she replaced Martha Argerich as soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Two years later, she signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon, and has since established her place among the world’s leading artists, with a succession of critically acclaimed performances and recordings. She was named Musical America’s Artist of the Year in 2017, and in 2021 received an Opus Klassik Award for her world-premiere recording of John Adams’ Must the Devil Have all the Good Tunes? with the Los Angeles Philharmonic under the baton of Gustavo Dudamel.

As a chamber musician, Yuja has developed long lasting partnerships with several leading artists, notably violinist Leonidas Kavakos, with whom she has recorded the complete Brahms violin sonatas and will be performing duo recitals in America in the Autumn. In 2022, Yuja embarks on a highly-anticipated international recital tour, which sees her perform in world-class venues across North America, Europe and Asia, astounding audiences once more with her flair, technical ability and exceptional artistry in a wide-ranging programme to include Bach, Beethoven and Schoenberg.

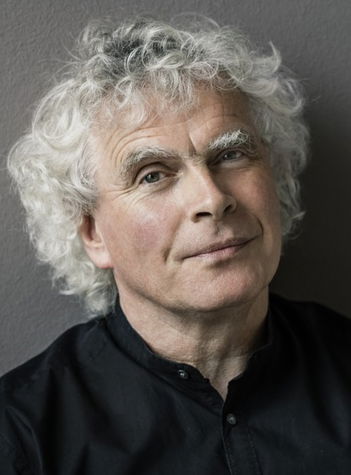

Simon Rattle conductor

We have seen one of today’s most distinguished conductors, Sir Simon Rattle, relatively often at the Rudolfinum in recent years. His long-term cooperation with the Czech Philharmonic has led to his appointment together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, as Artist-in-Residence for the 2022/2023 season. At his appearances with the Czech Philharmonic, he has performed a number of symphonic works and, most notably, compositions for voices and orchestra from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the repertoire for which Rattle has been the most acclaimed. He appeared most recently at the Rudolfinum in February 2024 with the pianist Yuja Wang, with whom he made a Grammy-nominated recording from their joint tour of Asia in 2017. From the 2024/2025 season, he becomes the Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

A native of Liverpool and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music has held a series of important positions in the course of his long career. He came to worldwide attention as the chief conductor of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he was employed for a full 18 years (for eight years as its music director); next came 16 years with the Berlin Philharmonic (2002–2018; artistic director and chief conductor) and six years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He opened the 2023/2024 season as chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with the title of “principle artist”, and he is the founder of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. Besides holding full-time conducting posts, he maintains ties with the world’s leading orchestras and gives concerts frequently in Europe, the USA, and Asia.

He has made more than 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics). He has won a number of prestigious international awards for his recordings including three Grammy Awards for Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which he recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Besides the prizes mentioned above, Rattle’s long-term partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic also led to the new educational programme Zukunft@Bphil, which has achieved great success. Even after moving on from that orchestra, Rattle did not abandon his engagement with music education, and he has taken part together with the London Symphony Orchestra in the creation of the LSO East London Academy. Since 2019, that organisation has been seeking out talented young musicians, developing their potential free of charge regardless of their origins and financial situation.

Compositions

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30

Sergei Rachmaninoff composed four piano concertos over a span of nearly half a century; the first dates from 1891 and the fourth, written in 1927, did not assume its definitive form until 1941. Rachmaninoff was one of the few 20th-century artists who was still continuing the tradition of composing piano virtuosos like Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, the Rubinstein brothers, and others from the previous two centuries. Rachmaninoff’s contemporaries Sergei Prokofiev and Béla Bartók were also examples of this, but unlike them, Rachmaninoff never abandoned the expressive resources of Romanticism in his composing. He remained faithful to the legacy of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whose influence we find in the breadth of the themes, the nostalgia of expression, and the orchestration. He also never left behind the influences of Russian folk music, something we also find in the works of Mussorgsky, Borodin, and others.

Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30, is regarded among pianists as one of the most difficult, and not only because of its technical demands (there are several passages with “ossia” versions, allowing performers to choose the more difficult or the easier option), but also because of its length. The concerto was dedicated to Józef (Josef) Hofmann, a pianist of Polish descent, but Hoffmann never played it. Rachmaninoff had composed it especially for his tour of the USA, where he wanted to present himself not only as a pianist, but also as a composer. The work was premiered on 28 November 1909 in New York with Walter Damrosch conducting and the composer at the piano, and it was heard again the following year on 16 January at Carnegie Hall in New York under the baton of Gustav Mahler. Rachmaninoff was extraordinarily impressed by Mahler’s approach. Although the orchestra had already rehearsed the composition, Mahler devoted himself to giving a precise reading of the work’s details. According to the musical author and composer Oskar Riesemann, Rachmaninoff commented: “Every detail of the score was important – an attitude too rare amongst conductors.” Shortly afterwards, the Piano Concerto No. 3 was given its Moscow premiere on 4 April 1910. The typically “Russian-sounding” opening theme is reminiscent of folk music or, according to some of Rachmaninoff’s biographers, an old Russian liturgical melody; the composer, however, did not agree with that characterisation. About the theme, he wrote to the musicologist Joseph Yasser: “It is borrowed neither from folk song forms nor from church sources. It simply ‘wrote itself’! You will probably refer this to the ‘unconscious’! If I had any plan in composing this theme, I was thinking only of sound. I wanted to ‘sing’ the melody on the piano, as a singer would sing it, and to find a suitable orchestral accompaniment, or rather one that would not muffle this singing.” The reprise of the sonata-form first movement deals primarily with this theme, while there is only a brief hint of the second theme. The nostalgic second movement is also typically Russian in character, and it leads without a break into the finale, which is again in sonata form. The composition is linked internally by a central idea that passes through all of the movements, and the second theme of the first movement reappears at the climax of the finale. The reemergence of these ideas creates the impression of ingenious improvisation that is so characteristic of Rachmaninoff. The wealth of the concerto’s harmonies, its masterful combination of homophonic and polyphonic writing, and brilliant orchestration all contribute to the work’s powerful effect.

Anton Bruckner

Symphony No. 6 in A major

Like the symphonies of Beethoven, the symphonies of Anton Bruckner constitute a self-contained whole. Some of Bruckner’s critics have described him as obsessive because he subjected all of his symphonies to revisions almost at the same time near the end of his life, as if they all represented one single work to him. Unlike in the case of Beethoven, where one can follow a direct line of development, and each symphony constitutes an individual entity, there are strong ties between Bruckner’s symphonies. His conception for them did not change over time, and one can find many links between them. The composer made his first attempt at composing a symphony in 1863, and his symphonic output ends with the incomplete work numbered as his Ninth Symphony, but if one includes this 1863 student work in F minor and the “Symphony No. 0” (more properly the “annulled” symphony) in D minor from 1869, he wrote eleven symphonies, and the chronology of their composing is confused by various versions of some of them. Bruckner is regarded as one of the last great symphonists of the 19th century whose works have become part of the standard repertoire and are regularly played, like those of Johannes Brahms, Antonín Dvořák, or Gustav Mahler (the latter overlapping into the 20th century). However, that did not come about quickly or without obstacles; Bruckner’s path to success in the concert hall was a difficult one. He did not begin to be fully accepted until after the performances of his Seventh Symphony by Arthur Nikisch in Leipzig in 1884.

The Sixth Symphony was composed between 1879 and 1881. The composer was able to hear it only once at an orchestral rehearsal of the Vienna Philharmonic, but before the actual concert, the conductor Otto Jahn decided to perform only the two middle movements. They were heard on 11 February 1883 in the Great Hall of the Musikverein, and the reception was ambivalent. Eduard Hanslick, a great proponent of Johannes Brahms and, as such, sceptical towards the “Wagnerian” Bruckner, expressed himself ambiguously: “...the composer has become a bit more disciplined, but he has lost his naturalness. In the Adagio, the audience’s interest and astonishment were still kept in balance, although with hesitation. However, in the oddity-laden Scherzo, the proverbial horse has thrown off its rider.” The first performance of all of the symphony’s movements took place in Vienna on 26 February 1899, again with the Vienna Philharmonic, this time led by Gustav Mahler, but in a version with cuts and revisions by the conductor. Today we cannot judge how drastic the changes were; Mahler’s version has not been preserved. Bruckner’s original version was first performed on 14 March 1901 in Stuttgart under the baton of Karl Pohlig, a native of the north-Bohemian city Teplice and a staff conductor at the Court Opera in Vienna during the first three years of Mahler’s directorship. That performance was also inadequate because the edition printed by the Viennese publisher in 1899 contained many errors. The first edition corresponding to the composer’s manuscript appeared in 1935, and that version of the symphony was first played on 9 October 1935 in Dresden, led by the Dutch conductor Paul van Kempen.

The first movement of the Sixth Symphony is built from three themes. In the development section, Bruckner shows himself to be a master of contrapuntal voice leading. The development section leads directly to the recapitulation followed by a majestic coda. It is in this symphony for the first time that the slow movement is central to Bruckner’s conception of the work, playing an important dramaturgical role and influencing the character of the other movements. It is based on the varied treatment of complexes of themes. The third movement (Scherzo) and the finale are related in character, and the third movement is especially engaging because of its colourful orchestration. In the final movement in modified sonata form, one again recognises several complexes of themes, the combination of which is the basis of the fanfare-like coda.