1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Semyon Bychkov

The Czech Republic joined the European Union in early May 2004. The Czech Philharmonic is celebrating that act by performing the composition from which the EU has borrowed its anthem. Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with its concluding Ode to Joy will be heard under the baton of Semyon Bychkov with soloists and the Prague Philharmonic Choir.

Programme

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 (70')

Performers

Lyubov Petrova soprano

Iwona Sobotka soprano

Lucie Hilscherová alto

Norbert Ernst tenor

Florian Boesch bass

Prague Philharmonic Choir

Lukáš Vasilek choirmaster

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Aftertalk

On Thursday, 2 May, after the concert, we invite you to an aftertalk and autograph session with the chief conductor Semyon Bychkov in the Ceremony Hall.

Moderated by Tereza Šindlerová.

For those who would like to attend the event but do not have a ticket for Thursday's concert and would like to spend more time in the Rudolfinum, we offer the opportunity to come from 19.30 for a guided tour of the Rudolfinum Gallery's Zhanna Kadyrov exhibition: UNEXPECTED.

CDs for signing will be available for purchase in the Ceremony Hall throughout the event.

Performers

Iwona Sobotka soprano

The Polish soprano Iwona Sobotka is a winner of the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels, one of the world’s most prestigious music competitions. Over the last 20 years, she has firmly established herself on concert and opera stages. A graduate of the Chopin University of Music in Warsaw and of the Escuela Superior de Música Reina Sofia in Madrid, she has been heard at New York’s Metropolitan Opera, Paris’s Opéra national, Berlin’s Komische Oper, and Madrid’s Teatro Real.

Her recent roles include Dvořák’s Rusalka. Sir Simon Rattle, with whom she has long been collaborating, has called her “A really unusual musician with a uniquely beautiful sound quality matched with fierce intelligence.” They have appeared together performing both the operatic (Wagner’s Parsifal) and concert repertoire. For example, with the Berlin Philharmonic she shined in Beethoven’s Christ on the Mount of Olives and Ninth Symphony; she has sung the Glagolitic Mass successfully with the Staatskapelle Berlin. She is also famed for performing the Polish vocal repertoire, and in the 2023/24 season, she served as the artist-in-residence for Poland’s Rubinstein Philharmonic.

Lucie Hilscherová mezzo-soprano

The Czech mezzo-soprano Lucie Hilscherová makes guest appearances at the National Theatre in Prague, the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava, the J. K. Tyl Theatre in Pilsen, the Silesian Theatre in Opava, the State Theatre in Košice, and the Mannheim National Theatre. She has also appeared as Háta in The Bartered Bride in Tokyo (2010, Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Suntory Hall, conductor Leoš Svárovský) and London (2011, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Barbican Hall, conductor Jiří Bělohlávek).

She is in demand for concert performances of the lieder and oratorio repertoire, and she also enjoys interpreting the works of contemporary composers. She has collaborated with important orchestras and conductors, appearing at such festivals as Musikfest Stuttgart, Beethovenfest Bonn, Grafenegg Musik-Sommer, Prague Spring, the Easter Festival of Sacred Music in Brno, Smetana’s Litomyšl, the St. Wenceslas Music Festival, and the Peter Dvorský International Music Festival in Jaroměřice.

Norbert Ernst tenor

Although the Viennese tenor Norbert Ernst is known mainly for the Wagnerian roles he has sung on the important opera stages of London’s Covent Garden, New York’s Metropolitan Opera, and the Bayreuth Festival, where he is a regular guest, his range of repertoire is broader. In previous seasons, he has also shined in the operas of Strauss and Mussorgsky at Milan’s La Scala and in Beethoven’s Fidelio in Sankt Gallen. His artistic versatility has been documented by a series of DVDs that record many of his performances at the Vienna State Opera, where he was an ensemble member from 2010 to 2017, including the CD “Lebt kein God” (2016) with arias from operas by Beethoven, Weber, and Wagner.

His discography is enriched by the album “Wohl fühl ich wie das Leben rinnt” with songs of the less traditional repertoire from the late-19th and 20th centuries, which he recorded with the pianist Kristin Okerlund. Concert solo performances and lieder recitals are a routine part of his professional life, with repertoire ranging from Bach’s Passion settings to Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde.

Norbert Ernst is a graduate of the Josef Matthias Hauer Konservatorium in Wiener Neustadt and of Vienna’s Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst.

Florian Boesch bass

The Austrian baritone Florian Boesch is a versatile singer in terms of genre and range of repertoire. This is perhaps best seen in his operatic roles, where he feels equally at home in Purcell or Weill, Mozart or Berg. Notwithstanding his many solo performances with distinguished orchestras and conductors, in the concert hall he has come to listeners’ attention mainly thanks to his close professional relationship with Nikolas Harnoncourt. He made his debut with the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/24 season as a soloist in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. His recordings reflect great interest in romantic song cycles, for the interpretation of which he has received such honours as the BBC Music Magazine Award. He is heard in song recitals at the festivals in Salzburg and Edinburgh, at Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, at New York’s Carnegie Hall, and at London’s Wigmore Hall, where he has also served as an artist-in-residence. Boesch received his vocal training first from his grandmother Ruthilde Boesch and then from Robert Holl at the Musikhochschule in Vienna. He now teaches at Vienna’s Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst.

Prague Philharmonic Choir

The Prague Philharmonic Choir (PPC), founded in 1935 by the choirmaster Jan Kühn, is the oldest professional mixed choir in the Czech Republic. Their current choirmaster and artistic director is Lukáš Vasilek, and the second choirmaster is Lukáš Kozubík.

The choir has earned the highest acclaim in the oratorio and cantata repertoire, performing with the world’s most famous orchestras. In this country, they collaborate regularly with the Czech Philharmonic and the Prague Philharmonia. They also perform opera as the choir-in-residence of the opera festival in Bregenz, Austria.

Programmes focusing mainly on difficult, lesser-known works of the choral repertoire. For voice students, they are organising the Academy of Choral Singing, and for young children there is a cycle of educational concerts.

The choir has been honoured with the 2018 Classic Prague Award and the 2022 Antonín Dvořák Prize.

Lukáš Vasilek choirmaster

Lukáš Vasilek studied conducting and musicology. Since 2007, he has been the chief choirmaster of the Prague Philharmonic Choir (PPC). Most of his artistic work with the choir consists of rehearsing and performing the a cappella repertoire and preparing the choir to perform in large-scale cantatas, oratorios, and operatic projects, during which he collaborates with world-famous conductors and orchestras (such as the Berlin Philharmonic, the Czech Philharmonic, the Israel Philharmonic, and the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic).

Besides leading the PPC, he also engages in other artistic activities, especially in collaboration with the vocal ensemble Martinů Voices, which he founded in 2010. As a conductor or choirmaster, his name appears on a large number of recordings that the PPC have made for important international labels (Decca Classics, Supraphon); in recent years, he has been devoting himself systematically to the recording of Bohuslav Martinů’s choral music. His recordings have received extraordinary acclaim abroad and have earned honours including awards from the prestigious journals Gramophone, BBC Music Magazine, and Diapason.

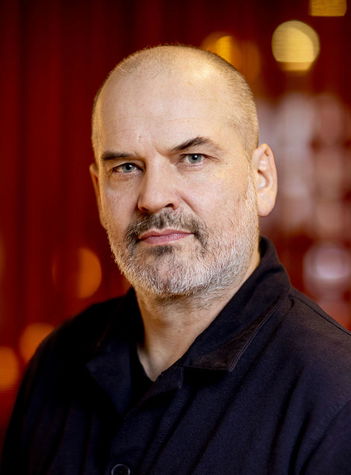

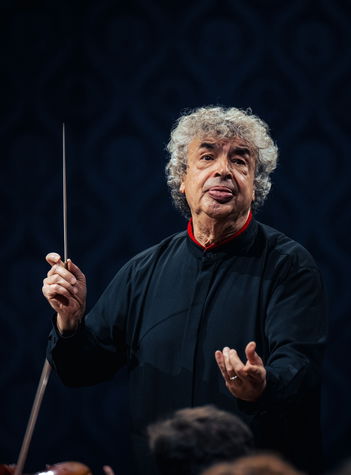

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125

Ludwig van Beethoven’s last completed symphony holds a special place in the history of the genre. The work was radical for its day, and its finale with choir and vocal soloists provoked contradictory reactions, becoming a clear turning point in the history of symphonic music. One can scarcely find a European composer who did not try to come to terms with this legacy, and the number nine seems to have acquired fatalistic associations for future generations. Robert Schumann went so far as to say that with his nine symphonies, Beethoven had taken the form’s development to a definitive conclusion. That did not turn out to be true, but many later composers paid tribute to the “Ninth”. Examples from the 19th include the finale of Johannes Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Richard Wagner’s inclusion of the symphony at the festival of his operas in Bayreuth, and Anton Bruckner’s symphonic “cathedrals”. Antonín Dvořák also professed admiration for Beethoven, writing to his friend Emil Kozánek in 1886: “I have a portrait of papa Beethoven hanging above my desk, and whilst composing I often gaze at it so that he might put in a good word for me up in heaven.” Seven years later, Dvořák honoured his hero in his last symphony, also a ninth, called “From the New World”.

What Beethoven put into his “Ninth” has not faded since its premiere on 7 May 1824 at Vienna’s Kärntnertortheater. To the contrary, through the work the composer has been a presence at many extraordinary events. One famous example was the celebration of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when players from leading orchestras of former East and West Germany, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, France, and the USA gathered to form a single ensemble for a performance of the work under Leonard Bernstein’s baton. For the event, Bernstein deliberately changed the word “Freude” (joy) in the text of the finale to “Freiheit” (freedom). In 1972, the melody of the “Ode to Joy” was approved by the Council of Europe as its anthem, and 13 years later, an instrumental version became the official anthem of the European Union.

The history of the Bohemian lands’ relationship with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony begins less than three years after its premiere. The first Bohemian performance took place while the composer was still living, on 9 March 1827 in the ballroom of the building U Vusínů on Masná Street in Prague’s Old Town, with students from the Prague Conservatoire conducted by the school’s director Friedrich Dionys Weber. A second Prague performance occurred ten years later at a concert at the Waldstein Palace, and a third was presented in 1842 by the Sophien-Akademie. František Škroup, composer of the Czech national anthem and Kapellmeister of the Estates Theatre, gave several performances of the “Ninth”, the last coming in 1860 at the farewell concert before his departure for Rotterdam. In 1886 Gustav Mahler excelled in the “Ninth” when he conducted the entire symphony by heart at a benefit concert at the Royal German Theatre (now the Estates Theatre). Later, Mahler was said to have “ruined” the work by making changes to the orchestration that the critics called a “desecration”.

Over the years, the Czech Philharmonic has played this symphony at nearly 170 concerts including foreign tours. The orchestra first played it on 22 March 1903 with its chief conductor Vilém Zemánek (1875–1922) at the Commodity Exchange, and most recently at last year’s Prague Spring Festival under the baton of Christoph Eschenbach. For many years, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was the work that traditionally closed the festival. The Czech Philharmonic played it at the festival for the first time in 1949 under the baton of Erich Kleiber, and since then it has played the work at 30 Prague Spring Festival performances, repeatedly with its music director Václav Neumann as well as with, for example, Karl Böhm, Zubin Mehta, Carlo Maria Giulini, and Wolfgang Sawallisch. Leonard Bernstein gave a legendary festival performance in June 1990, just a few months before the conductor’s death. Many listeners will certainly remember the emotionally charged Concert for Civic Forum with Václav Neumann in December 1989 in Smetana Hall at the Municipal House during the Velvet Revolution, which was recorded live by Supraphon. As the Ode to Joy was being played, the future President of Czechoslovakia and later President of the Czech Republic Václav Havel took the stage to introduce the new government. The symphony was one of Havel’s favourite compositions, and an arrangement of it was heard at his funeral on 23 December 2011. It would be a pity not to mention the 1930 performance of the “Ninth” with the Czech Philharmonic led by the composer Alexander Zemlinsky for the celebration of the 80th birthday of the first President of Czechoslovakia T. G. Masaryk at Prague’s Lucerne Palace. Five years later, during the era of the orchestra’s noted manager Jaromír Žid (1893–1981), the orchestra played the symphony under the baton of Bruno Walter, a composer and close associate of Mahler.

The Czech Philharmonic has recorded the symphony on the Supraphon label with Paul Kletzki (1964) and with its chief conductors Václav Neumann (1989) and Vladimir Ashkenazy (live recording of the performance on 17 November 1999 for the tenth anniversary of the Velvet Revolution). The work was recorded live in Tokyo in 1972 by Denon, and a recording was made in 2013 for Exton with Ken-Ichiro Kobayashi. A restored archival recording from the 1951 Prague Spring Festival with the conductor Herrmann Abendroth has been issued on the Radioservis label (2014).

Without exaggeration, we can call Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony his life’s work. He wrote it between 1822 and 1824, but the seminal idea for the composition dates back more than 30 years. Around that time, Beethoven became familiar with the poem An die Freude by Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805) and began to contemplate setting it to music. He wrote down ideas in his sketchbook and returned to the poem continually; he was simply fascinated by it… Meanwhile, he was discovering the possibilities of symphonic music, and at a benefit concert that he gave in December 1808 at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien, he tried out the combination of vocal and orchestral elements in his Choral Fantasy for piano, vocal soloists, choir, and orchestra, Op. 80. Here one finds variations on a tune that strikingly resembles the famous melody of the Ode to Joy. Beethoven brings up this connection in a letter dated 1824: “…I am setting Schiller’s immortal ‘Lied an die Freude’ to music in the same way that I did in my piano fantasy with choir, but on a much larger scale.” In 1808 he finished his Fifth and Sixth, and he wrote two more symphonies four years later. Whilst composing his Eighth, he already had another symphony in mind, and he knew he wanted to write it in the dramatic key of D minor. And although he often composed several works at the same time, and we find comments in his sketchbook about a tenth symphony, that work remained only in the form of sketches.

In 1817, the Philharmonic Society of London commissioned two new symphonies from Beethoven. At the time, the circumstances of the composer’s life were quite unfavourable. Besides suffering from total hearing loss, he was also dealing with complicated family disputes, including one with the widow of his deceased younger brother Kaspar over the guardianship of the nephew Karl. The lawsuit dragged on for five years. The composer descended into a deep creative crisis, compounded by fevers, rheumatism, and eventually jaundice. He was finally rallied by commissions for new works and the prospect of an improvement to his finances. Two major works appeared, the Missa solemnis, Op. 123, and the Diabelli Variations, Op. 120, for piano solo. Then came the Ninth Symphony, which was dedicated to Friedrich Wilhelm III (1770–1840), King of Prussia, and which preoccupied Beethoven nearly until his last breath; on 18 March 1827, just a week before his death, he sent a letter to London with the metronome markings.

This symphony went beyond anything in the genre that had preceded it in terms of length, the size of the forces, and dynamism. The composer linked all the movements together with musical material heard at the outset, binding them together so tightly that one movement cannot exist without the others. The tempestuous second movement supplements and builds upon the first, and its middle section (Trio) prepares the atmosphere of the following movement (Adagio molto e cantabile), which calms listeners before the climactic conclusion. In the finale, the composer “borrows” from the previous movements not only thematic, but also structural elements, building something that must have sounded like a chaotic patchwork to many of his contemporaries. His incredibly daring treatment of content and form was crowned by the message of Schiller’s Ode to Joy about the steadfastness of the human spirit. To say the least, it must have been surprising when the score of enormous dimensions arrived in London from Vienna, with the additional requirement of a choir and soloists singing in German. The English performed the work with the conductor Sir George Smart (1776–1867) on 21 March 1825, after the Viennese premiere, but they had the words translated into Italian. A version in English came later.