1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Concert with residents of the season

Magdalena Kožená has included songs by Bohuslav Martinů on the programme of her special concert to draw attention to the beauty of this seldom heard music. Simon Rattle has a similar motivation with Robert Schumann, whose music is not often heard at the Rudolfinum.

Programme

Robert Schumann

Genoveva, Op. 81, overture to the opera (10')

Bohuslav Martinů / arranged for orchestra by Jiří Teml

Songs on One Page, H 294 (8')

Bohuslav Martinů

Nipponari. Seven songs to Japanese lyric poetry for female voice and small orchestra, H 68 (21')

— Intermission —

Robert Schumann

Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61 (38')

Performers

Magdalena Kožená mezzo-soprano

Simon Rattle conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

“To me, Schumann is the perfect essence of everything one understands by the word Romanticism. His music is deeply passionate and communicative, but it never descends into self pity. I don’t think there are many more moving compositions than the Adagio of Schumann’s Second Symphony. Unlike Mahler, he never gets caught up with himself emotionally, but the music he produces is like a crystal-pure extract. It is one of the loveliest symphonies I know, and one of the most difficult to perform”, says Sir Simon Rattle.

Performers

Magdalena Kožená mezzo-soprano

Like on many past occasions, Magdalena Kožená is returning to her homeland with her husband, Sir Simon Rattle. Kožená, a graduate of the Brno Conservatoire and of the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava, came to worldwide attention thanks in part to victory at the International Mozart Competition in 1995; four years later she signed an exclusive contract with the label Deutsche Grammophon, for which she has released many award-winning recordings (Gramophone Award, Echo Klassik, Diapason d’Or etc.). She divides her performing activities between recitals, concert appearances, and operatic roles including regular guest appearances at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. She also performs in such non-classical genres as swing and flamenco. Her classical repertoire is of remarkable breadth, ranging from the baroque era and collaborations with ensembles specialising in early music to the classical and romantic repertoire, in which she has won fame in part as a proponent of Czech music, and onwards to the music of today.

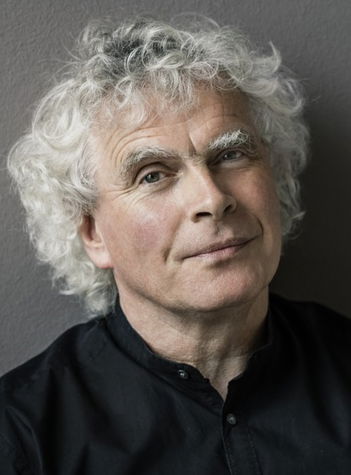

Simon Rattle conductor

We have seen one of today’s most distinguished conductors, Sir Simon Rattle, relatively often at the Rudolfinum in recent years. His long-term cooperation with the Czech Philharmonic has led to his appointment together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, as Artist-in-Residence for the 2022/2023 season. At his appearances with the Czech Philharmonic, he has performed a number of symphonic works and, most notably, compositions for voices and orchestra from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the repertoire for which Rattle has been the most acclaimed. He appeared most recently at the Rudolfinum in February 2024 with the pianist Yuja Wang, with whom he made a Grammy-nominated recording from their joint tour of Asia in 2017. From the 2024/2025 season, he becomes the Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

A native of Liverpool and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music has held a series of important positions in the course of his long career. He came to worldwide attention as the chief conductor of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he was employed for a full 18 years (for eight years as its music director); next came 16 years with the Berlin Philharmonic (2002–2018; artistic director and chief conductor) and six years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He opened the 2023/2024 season as chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with the title of “principle artist”, and he is the founder of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. Besides holding full-time conducting posts, he maintains ties with the world’s leading orchestras and gives concerts frequently in Europe, the USA, and Asia.

He has made more than 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics). He has won a number of prestigious international awards for his recordings including three Grammy Awards for Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which he recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Besides the prizes mentioned above, Rattle’s long-term partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic also led to the new educational programme Zukunft@Bphil, which has achieved great success. Even after moving on from that orchestra, Rattle did not abandon his engagement with music education, and he has taken part together with the London Symphony Orchestra in the creation of the LSO East London Academy. Since 2019, that organisation has been seeking out talented young musicians, developing their potential free of charge regardless of their origins and financial situation.

Compositions

Robert Schumann

Genoveva, Op. 81, overture to the opera

There are some opera overtures that live a more active life on the concert stage that the operas to which they belong. This is also the case with the only opera by the German Romantic composer Robert Schumann, Genoveva, Op. 81. The opera has not found a place in the theatrical repertoire, and it has never been fully rehabilitated in spite of numerous recent attempts, but the overture quickly won recognition. The music critic Eduard Hanslick, already an important figure at the time, was of the opinion that the overture was the most successful part of the opera, and Schumann was also aware of its potential from the beginning. Schumann took the subject matter of a medieval legend about Genoveva of Brabant, shaping it into a libretto based on literary models by Ludwig Tieck and Christian Friedrich Hebbel from the first half of the 19th century.

The premiere took place in Leipzig in late June 1850, but the production was withdrawn from the repertory after a few performances. Schumann was certainly disappointed by the failure because he had spent a long time developing the idea for an opera and had considered various subjects before choosing Genoveva. He wrote it in the complicated atmosphere of the years 1847 and 1848, when the mentally ill composer’s mood was fluctuating severely, affecting his ability to engage in creative work. The story of Wagner’s Lohengrin (first performed in Weimar in August 1850) shares points in common with Genoveva, and it also overshadowed Schumann’s opera. As we know, however, the overture was given several concert performances and may have appeared in print even before the premiere of the opera itself. In the overture, Schumann uses the characteristic motifs of two main characters—Genoveva and the treacherous Golo. The music’s progression from C minor to C major follows the storyline: after dark and dramatic twists and turns, the opera’s climax is the joyous reunion of the married couple Siegfried and Genoveva.

Bohuslav Martinů

Songs on One Page, H 294

Bohuslav Martinů wrote his Songs on One Page, a cycle of seven songs for voice and piano with texts from Moravian folk poetry (“after Sušil”), during the Second World War in February and March 1943. The cycle is dedicated to the wife of the Czechoslovak ambassador in Washington, Olga Hurbanová. To this day, these short love poems and the almost mystical Sen Panny Marie (Dream of the Virgin Mary) captivate readers with their simplicity, novelty, and succinctness. Martinů set them to music in a similar vein, closely coupling the music to the words. Together with the New Chap-Book (1942) and the Songs on Two Pages (1944), this cycle is among the compositions that reflect the composer’s reminiscences of his homeland. The Songs on One Page were published in 1948 by Melantrich, but they did not escape politically tinged criticism from the pen of Antonín Sychra, who saw them as “artificially constructed greenhouse products” (1949). How wrong he was is shown by the enduring popularity of these lovely miniatures with amateur singers and concert artists. In 1997, at the request of Ilja Šmíd, executive director of the PKF — Prague Philharmonia, the Czech composer Jiří Teml (* 1935) prepared an orchestration of the Songs on One Page, demonstrating his understanding of the style of other composer and his great experience with orchestration. Magdalena Kožená gave the first performance of the songs in this arrangement.

Bohuslav Martinů

Nipponari – Seven songs to Japanese lyric poetry for female voice and small orchestra, H 68

Martinů’s first attempt at the genre of songs accompanied by a larger or smaller instrumental ensemble was the seven-part cycle Nipponari, H 68, which he wrote in the summer and autumn of 1912 as a 22-year-old youth who had not yet completed his studies at the conservatoire and was dividing his time between Prague and his birthplace Polička. In the cycle, he built upon experience from his early songs composed for voice and piano, which are numerous but not very important. For the most part, he wrote musical settings of Czech love poetry (by J. V. Sládek, A. E. Mužík, V. Hlavsa etc.) and of symbolist verses or folk poetry in some exceptional cases. Martinů’s earliest preserved song dates from 1910 (Než se naděješ, H 6). In Nipponari, the composer took inspiration from old Japanese poems, with which he became acquainted through a Czech translation by Emanuel z Lešehradu (Nipponari, ukázky žaponské lyriky, 1909). At the same time, he fell under the influence of French Impressionism and of Debussy’s La mer, piano music, and songs in particular. He also knew Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly, of course; in 1920 he even contemplated writing an opera with “Japanese” subject matter based on Jan Havlasa’s novel Okna do mlhy (Windows into the Mist), but nothing ever came the idea.

In Nipponari, the voice (in the mezzo-soprano range) is accompanied by a small orchestra consisting of flutes, English horn, triangle, tam-tam, celesta, harp, and piano reinforced by a string section, but the instrumentation of the individual songs is variable. The main goal is to portray a dreamy atmosphere. Scenes of nature are poetically intermingled with images of daily life. The songs are in a different order in the composer’s version for voice and piano (Prague, 1912). Martinů dedicated the work to Theo Drill-Oridge, a vocal soloist with the opera companies in Vienna and Berlin. She enchanted Martinů when she appeared on the stage of the National Theatre in Verdi roles (1911) and again a year later in operas by Gluck and Wagner.

Robert Schumann

Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61

Robert Schumann also gets the last word on today’s programme, this time as a symphonic composer. His Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61, dates from 1845–1846; it is the third of Schumann’s four symphonies chronologically. The symphony was written in Dresden, where Robert and Clara had moved from Leipzig, hoping to find peace and quiet for composing, societal recognition, and a sympathetic public. However, the year 1845 was marred by the composer’s severe depression, and his struggle with it was also reflected in his work on the symphony. While Genoveva is sometimes compared to Beethoven’s Leonore, Schumann’s Symphony in C major has a counterpart in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The work is dedicated to King Oscar I, King of Sweden and Norway from the House of Bernadotte, who succeeded his father as king in 1844 and was himself, incidentally, a composer. Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy conducted the symphony’s first performance on 5 November 1846 at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. The first movement begins with a brass chorale, which leads to the sharply rhythmic Allegro. The following Scherzo has two trios, the second of which develops the B-A-C-H motif, as if his previous work for organ, Six Fugues on the Name B-A-C-H, Op. 60, had not entirely disappeared from his memory. The third movement with its contrapuntal middle section flows along broadly in the melancholy key of C minor. The fourth movement, written in sonata form just like the first movement, unifies the whole symphony motivically, and the work ends with a majestic coda.

The corrections of the Second Symphony before its publication and the making of arrangements for piano four- and eight-hands, revised by the composer in 1848, date to the same period as the composition of Genoveva. The two works share in common not only the period when they were written, but also, most importantly, a similar message about the victory of good over evil.